Growing up, I spent my days traversing between the hearing and deaf worlds; today I often write about topics that intersect with deafness. My family has two generations of genetic deafness, and I grew up with the understanding that deafness and American Sign Language were powerful, vibrant, and enabling. My deaf family members never seemed more comfortable, more alive, more themselves than when they were signing among deaf people.

But often, from the outside, other people saw only disability. They believed there was no way to communicate with my family members and so they never connected with them; they never found a way to listen. Because of this, I've witnessed my family members' civil rights violated, sometimes in life-threatening ways.

My connection to questions of access, language, and power are rooted in stories passed down to me—especially by my mother, grandmother, and great aunt. And they all come together in my memories of my grandfather, who was my fishing buddy, my personal carpenter, and my best friend in the special way that grandparents can be to children.

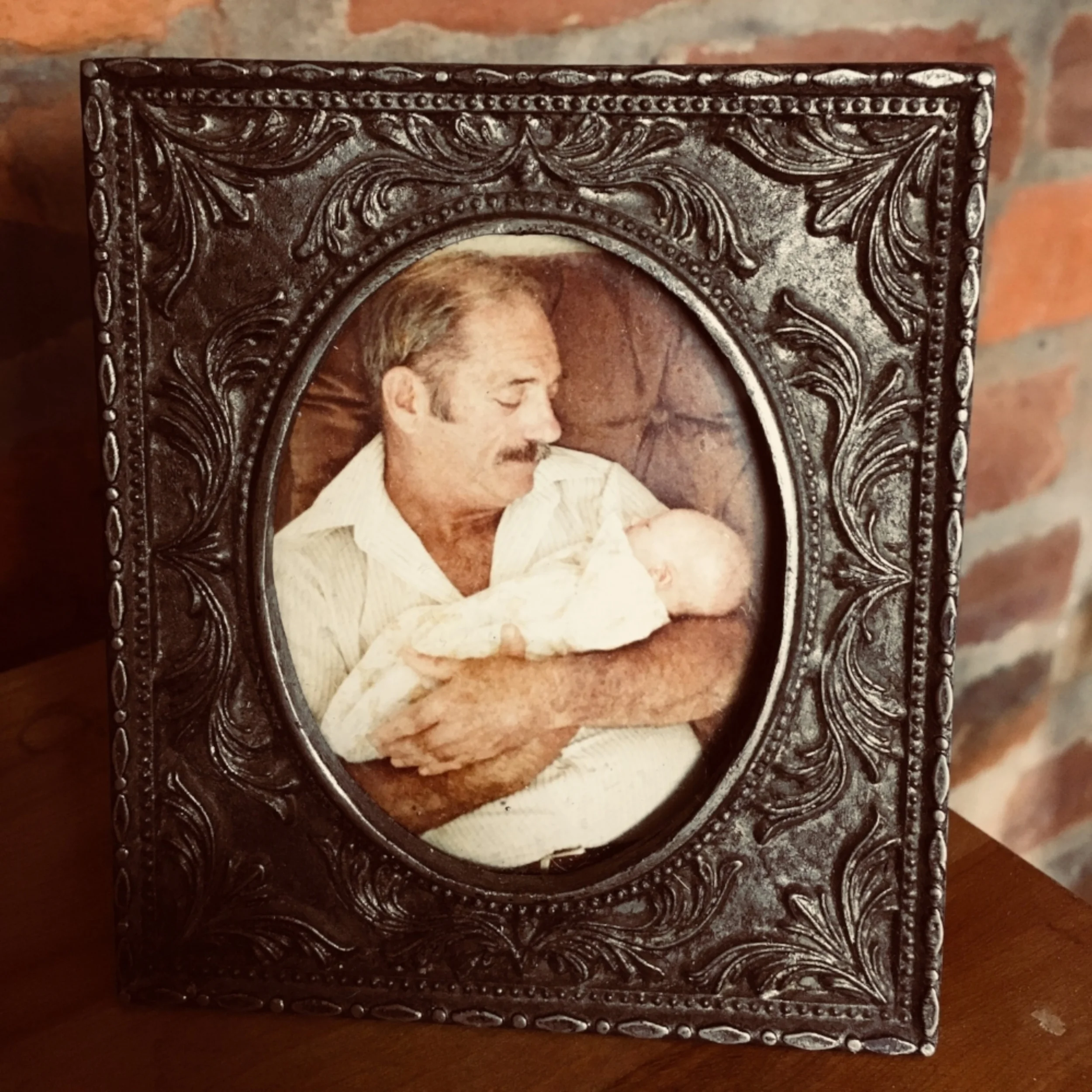

Whenever I wonder what I’m doing, or why I’m doing it, I look at this photo of my grandfather holding me when I was a baby. This photo has never been far from me—whenever I leave home for any significant amount of time, it comes with me. He was one of the most tender men I’ve known, full of grace and love. But he was language-deprived, struggled to be promoted in his job, and faced absolute horrors in hospitals. Thinking of these types of violence that were enacted on him motivates me to try to help people understand a little more about deafness, deaf culture, and American Sign Language, as well as the history of their oppression and suppression.

I’ve tried to do this in a way that focuses on both the expertise and resistance of deaf people, and the ways hearing people’s good intentions often go terribly awry. My book, The Invention of Miracles: Language, Power, and Alexander Graham Bell’s Quest to End Deafness, does this through the lens of Alexander Graham Bell’s lifelong attempts to dismantle the deaf community; my essays look at a variety of more contemporary issues. A common way people describe my writing is to say it focuses on deafness, but it may be more accurate to say that it focuses on hearing people—our unexamined privilege, our abuses of power, the harmful ways we habitually turn away.

I am a part of that. I have to recognize that I come to this work with a certain amount of power that is centered on my ability to hear. I am not deaf. I am not hard of hearing. My experiences are adjacent to deafness, but I have always experienced life as a hearing person. I've found that other hearing people turn to me to answer questions about deafness, even if there is a deaf person standing beside me who is undoubtedly more qualified to answer. I've learned that without being careful, my words could supplant deaf voices instead of joining them. That is not my intention; I hope my work will connect to (not replace) the significant body of work by deaf, DeafBlind, and hard of hearing writers, who are very capable of speaking and writing for themselves. To that end, I want to point towards some resources for finding your way into that body of work, if you haven’t already.

Whenever I’m treading into new literary waters, I like to begin with anthologies, which allow me to dip into a whole variety of different pieces and see whose voices or perspectives intrigue me. Here are a few top-quality anthologies featuring some of the best deaf, DeafBlind, and hard of hearing writers:

Another great way to read a variety of contemporary writers would be to peek into the literary journals Wordgathering (which focuses broadly on disability) and The Deaf Poets Society. For a wide array of books and DVDs on deafness, check out the presses Gallaudet University Press, Dawn Sign Press, and HandType. There are many amazing deaf and hard of hearing writers in the literary world—both historically and today—and they are working in all genres to create powerful, potentially world-changing art.

I really do believe that listening (in whatever form that takes) is one of the most politically powerful things we can do; just as being listened to is one of the most empowering experiences we can have. We can listen through spoken or signed or written languages; through quiet observation; through our ears, our eyes, or our fingers.

One thing deaf culture has taught me is that there are infinite ways to listen and learn from and love each other; in my experience, deaf people know this almost innately. I often wonder what it would be like if hearing people grasped this concept as easily. I wonder how my grandparents' lives would have been different if more people took the time to try to understand them the way that they so often worked to understand others.